At Temeke Hospital in Tanzania, a shift in oxygen access is helping close one of the most persistent gaps in universal health coverage. As part of a new regional initiative, the hospital is moving away from costly oxygen cylinders toward a more reliable, affordable supply – with benefits that will extend across East and Southern Africa.

Every day, thousands of patients walk through the doors of Temeke Regional Referral Hospital in Dar es Salaam. Serving a population of 1.7 million, the hospital has long struggled with an invisible but life-saving challenge: oxygen.

“Oxygen is a medicine,” says Chief Medical Officer Dr. Joseph Kimaro. “It’s essential for survival in nearly every critical situation, from resuscitation to neonatal care. But it’s expensive. It’s heavy. And it’s not always there when we need it.”

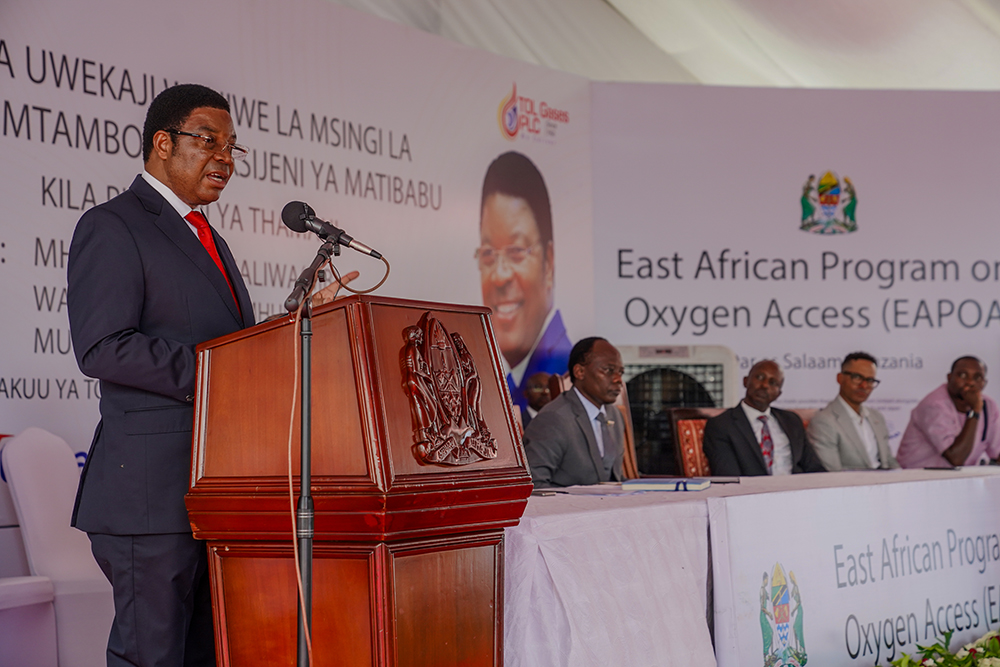

That’s beginning to change – not just for Temeke, but for hospitals across the region. Tanzania and Kenya are now center stage in Africa’s first regional effort to produce and distribute liquid medical oxygen. The second phase of the East African Program on Oxygen Access (EAPOA), funded by Unitaid and implemented by the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), goes beyond infrastructure. It’s a forward-looking development model: locally driven, self-sustaining, private sector-powered and built to last.

Launched in Kenya in 2024, the EAPOA aims to revolutionize oxygen access across East and Southern Africa through a regional production and distribution model. But to appreciate its significance, it helps to understand how oxygen reaches patients today.

Medical oxygen is critical for treating pneumonia, childbirth complications, preterm birth, COVID-19, severe malaria, and advanced HIV. Yet many hospitals across sub-Saharan Africa access only a fraction of what they need, often relying on individual metal cylinders filled with compressed gas. These cylinders are costly to refill, vulnerable to theft, prone to leakage, and must be carried by hand, constantly monitored, and frequently replaced – making them inefficient and prone to disruption. In under-resourced clinics, it’s common for multiple patients to share a single cylinder – often without proper flow meters to regulate dosage. This can lead to underdosing, oxygen toxicity, or, in the worst cases, fatal outcomes.

“If you go to the ward, you’ll find three, four, five cylinders, even 10 sometimes, because you have so many patients needing oxygen,” says Salha Omary, a pediatrician in Temeke’s neonatal intensive care unit. “Sometimes a patient needs oxygen, but there’s no cylinder. Or there is one, but it’s empty. Or it’s leaking. Or you don’t have the right regulator”.

“It’s not just the cost, it’s the time,” she adds. “You send someone to collect the cylinder. It’s heavy. They come back, and it’s not full. Or the connector doesn’t fit. It’s a daily stress.”

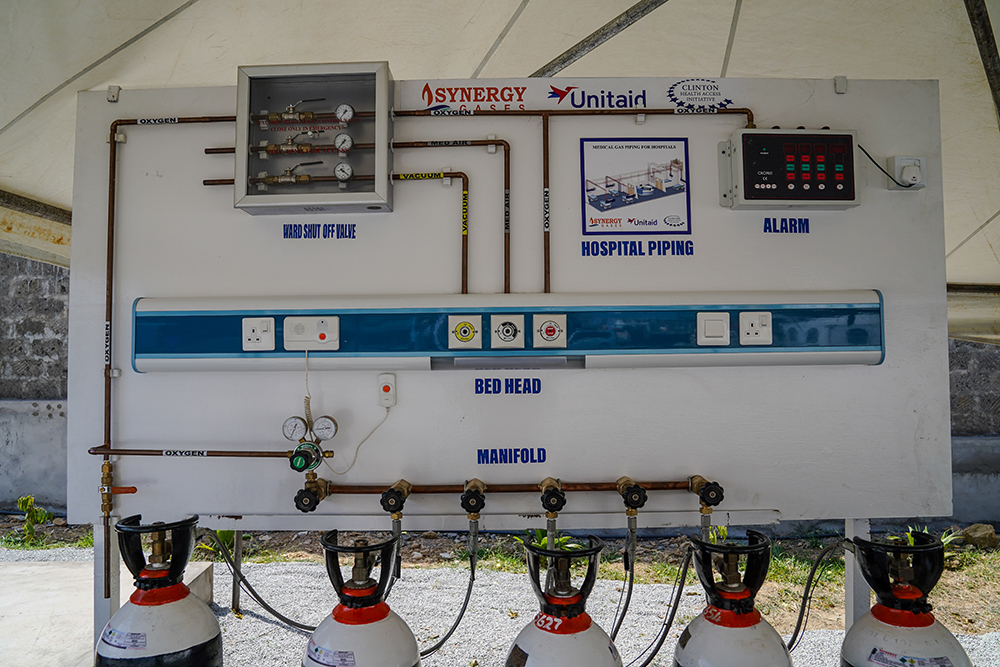

Liquid medical oxygen is a more efficient, reliable alternative. Produced by cooling ambient air in an air separation unit, it is stored in insulated tanks and converted back to gas at the point of use. One liter expands to about 830 liters of pure oxygen gas when warmed, enough to safely supply multiple patients via piped systems at controlled doses. But this system requires infrastructure.

While standard in high-income countries, sub-Saharan Africa has struggled due to a lack of oxygen production facilities and a limited market for liquid oxygen. The small number of industrial gas companies producing oxygen often prioritize commercial over medical supply, keeping prices high and access limited.

In Tanzania, most public facilities rely on purchasing individual cylinders. Temeke Hospital alone spends up to 32-35 million Tanzanian shillings (US$11,000-13,000) per month on oxygen – a significant portion of hospital operating costs. And yet, says Dr. Kimaro, “Only two departments have piped-in supply. The rest carry around cylinders. They are dangerous. They are inefficient.”

The EAPOA is working with local gas suppliers to establish high-capacity air separation units that serve as central ‘hubs’, supplying liquid oxygen to surrounding health facilities and regional refilling hubs, i.e. the ‘spokes’, through bulk tanks and delivery networks.

Together, this flexible network strengthens supply chains, lowers costs, and builds a sustainable market for liquid oxygen across the region.

New facilities at TOL Gases in Dar es Salaam are set to come online in 2026, increasing the supply of high-purity oxygen and reducing the reliance on imported or industrial-grade alternatives – for Temeke Hospital and many more like it in the region.

“This is not just a donation of tanks. This is production, distribution, pricing and use – all covered,” says Rose Rutizibwa, CHAI’s Monitoring and Evaluation Officer in Tanzania.

Unitaid’s US$22 million investment in the EAPOA will add 13 tons of daily oxygen production capacity in Tanzania. Implementation support from PATH and CHAI, along with government collaboration, will ensure this supply is affordable – 30 to 50% lower than current cylinder-based models. Beyond expanding production, the investment is helping to build the resilient, locally anchored oxygen ecosystem Rose describes – one that reduces system-wide costs and improves reliability across the supply chain.

These savings matter. In Tanzania’s public hospitals, oxygen is free to patients, meaning the government bears the full cost. “If we can reduce our bill by half,” says Dr. Kimaro, “we can reinvest in other areas – neonatal ventilators, patient monitors, better infrastructure. We can save more lives.”

Temeke Hospital will soon serve as both a recipient and supplier of oxygen. Through support from the Ministry of Health, a new pressure swing adsorption plant with an on-site cylinder filling station is being installed, allowing the hospital to supply surrounding lower-level health facilities.

Meanwhile, Temeke will benefit from cheaper liquid oxygen through the EAPOA. USAID’s EPIC project will install bulk storage tanks and bedside piping in five additional wards – complementing the broader EAPOA rollout and ensuring that once oxygen arrives, it reaches patients safely and efficiently. These efforts, supported by a range of partners, illustrate how the EAPOA is strengthening investments in oxygen access across the health system.

At the national level, Tanzania’s Prime Minister Kassim Majaliwa has welcomed this shift: “This project will improve the availability of medical oxygen across the country, reaching even district-level facilities. It will reduce deaths caused by respiratory diseases, including maternal deaths, ultimately saving the lives of women and children in our country.”

Rose agrees. “Before, some suppliers had to import oxygen from as far as Dubai. Now we’re producing it here. And not just for Tanzania – this supply will reach neighboring countries too.”

The EAPOA is more than just a health infrastructure project. It represents a new model for global health development, one where countries lead the way, partnerships are rooted locally, and private sector capacity is prioritized. With smart financing and coordinated systems, the program is building a stable, self-sustaining oxygen market, improving health outcomes and economic resilience.

“This is a catalyst,” Rose says. “It’s not just about oxygen. It’s about what’s possible when we think bigger.”

And for Dr. Kimaro, the change can’t come soon enough: “With this program, oxygen becomes what it should always be – available, affordable, and there when a life depends on it.”