When the World Health Organization (WHO) launched its Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer in 2020, it challenged every country to build the systems that would make this possible and take coordinated action across three pillars: vaccination, screening and treatment. Cervical cancer is one of the few cancers that can be both prevented and cured, yet it still claims more than 300,000 women’s lives worldwide every single year.

“Eliminating any cancer would once have seemed an impossible dream,” said WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus at the time. “But we can only eliminate cervical cancer if we match the power of our tools with unrelenting determination to scale up their use globally.”

In Rwanda, that determination is paying off – and providing inspiration for what elimination can look like in practice.

A system, not a slogan

Rwanda’s groundwork began long before WHO’s global call to action. In 2011, it became the first country in Africa to introduce a nationwide vaccination program against HPV – the infection that causes nearly all cases of cervical cancer. Within a few years, the program covered more than 90% of eligible girls in the country – among the highest rates in the world.

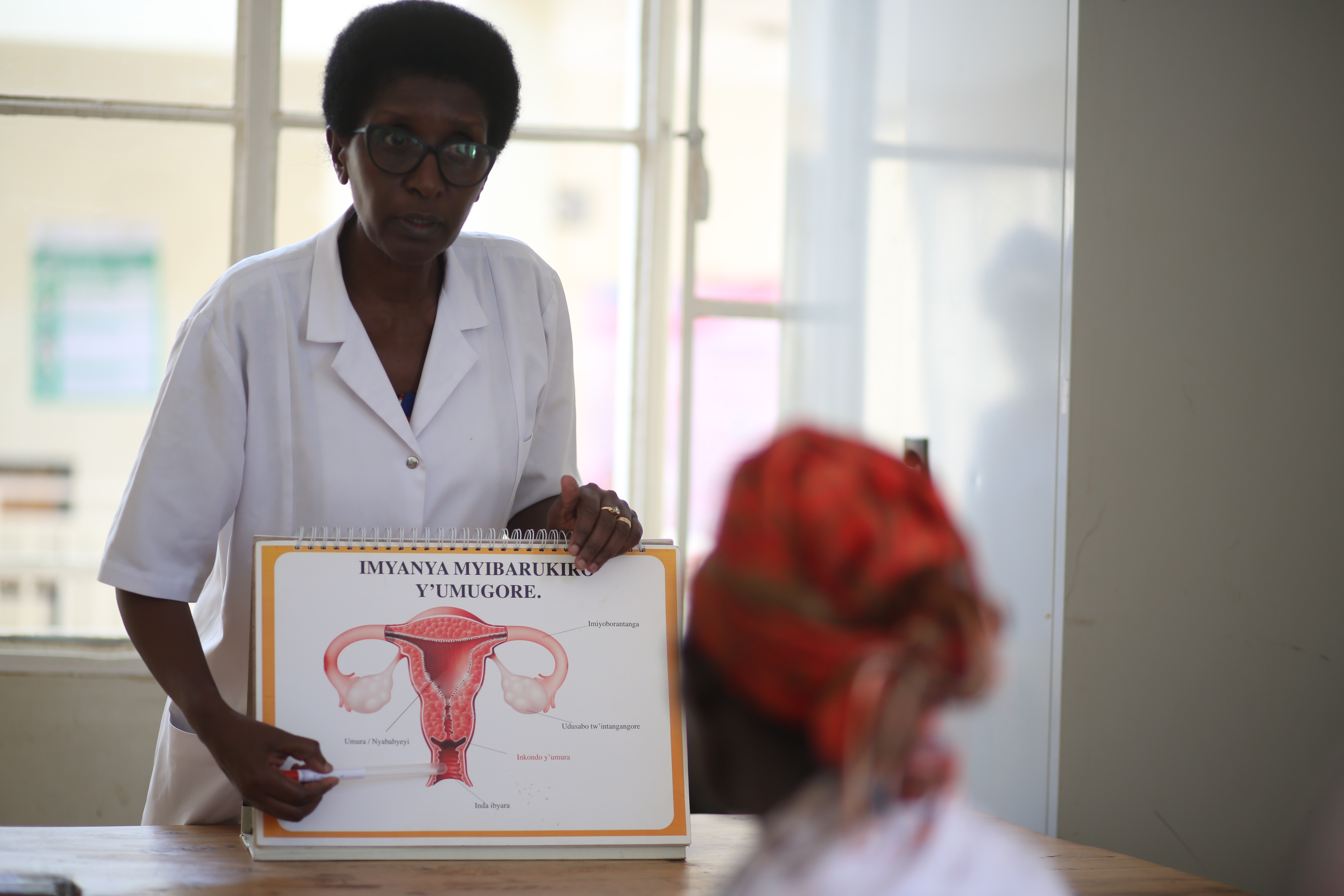

With vaccination established, Rwanda moved to expand screening and treatment. Working with different partners, including, among others, the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) and backed by catalytic funding from Unitaid, the Ministry of Health was able to build a system capable of reaching women across the country. The approach integrates affordable HPV DNA testing, community-based self-sampling, portable treatment devices, and digital patient tracking – all anchored in Rwanda’s universal health insurance scheme.

"In Rwanda, cervical cancer elimination is no longer a slogan,” says Dr. François Uwinkindi, Non-Communicable Diseases Division Manager at the Rwanda Biomedical Center. “It’s a system in action. We’ve built an approach that begins at the community level – with education, self-sampling, and screening – and extends all the way to diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Every step is linked; every woman is accounted for. That’s how elimination becomes achievable, not theoretical."

The power of political will

Rwanda’s success stems from political leadership and a belief that women’s cancers should never be death sentences. The Ministry of Health made cervical cancer prevention a national priority, embedding it in the country’s universal health coverage agenda. The country commitment is further translated in the Accelerated Plan for Cervical Cancer Elimination in Rwanda “Mission 2027” aiming at achieving the global cervical cancer elimination targets by 2027.

"New technologies such as HPV DNA testing and modern treatment devices changed the pace of what was possible,” says Dr. Uwinkindi. “We started in five districts with Unitaid’s support and today the country has expanded screening and treatment to almost every district. Rwanda moved quickly because the government saw that elimination was achievable — not in theory, but in practice."

Unitaid moved early. In 2019 – responding to Dr. Tedros’s 2018 global call for action to eliminate cervical cancer – it committed US$70 million to jumpstart affordable HPV screening in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Rwanda. HPV tests are the most accurate way to identify if a woman is at higher risk of developing cervical cancer and they perform significantly better than the alternative subjective screening method that relies on visual inspection of the cervix. Through Unitaid’s market-shaping role, Rwanda secured steep price reductions, bringing screening within reach for all women. These tests are now included in Rwanda’s community-based health-insurance scheme.

“We realized elimination wouldn’t be sustainable unless screening and treatment were covered by national health insurance,” says Sylvie Gaju, CHAI’s lead for women and children’s cancers. “We worked for five years to make that happen – and now it’s finally included.”

That inclusion is a gamechanger; ensuring that elimination will not depend on external aid but on the country’s own health-financing system.

Innovation on the front line

Replacing bulky cryotherapy machines with lightweight, battery-powered thermal ablation devices has been another breakthrough. Unitaid and partners negotiated agreements reducing the cost of these portable tools by nearly 45% and supported their introduction across more than 20% of LMICs.

"Before, women had to travel to district hospitals for pre-cancerous lesions treatment where cryotherapy machines were available,” explains Dr. Uwinkindi. “Now nurses can treat women in local health centers – even in outreach tents – saving time, money, and lives."

Each handheld device fits in a small backpack, runs for hours on a rechargeable battery, and treats precancerous lesions in about a minute.

The backbone: Community health workers

Rwanda’s 60,000 community health workers are the engine of success. They educate women, distribute self-sampling kits, and ensure follow-up after positive results. In rural areas, self-sampling has made a big difference, showing that women can take samples themselves at home.

“Reaching rural women means going to where they are,” says Dr. Uwinkindi. “We set up screening tents where women work so they don’t have to lose a day’s income to be screened at the health facilities.”

Through outreach initiatives, screening now happens in cooperatives, workplaces, local community gatherings and open-air markets. Each woman screened and treated for precancerous lesions is, as Gaju puts it, “a cancer averted.”

For 31-year-old Perpetue Uwingabire from Musanze District, that accessibility made the difference. “I didn’t know much about cervical cancer until the community health worker came to my home,” she recalls. “I took the self-sampling test and was called back for results and treatment at my health center. The nurse explained everything and treated me the same day. If the service had been far away, I might not be here now. Now I tell every woman I meet – don’t wait, go for screening.”

Behind the scenes, a national electronic registry quietly tracks every test, treatment, and follow-up. “Rwanda’s digital patient-level system makes real-time monitoring possible – a major leap over countries where data still sits on paper,” says Dr. Uwinkindi. Few nations can claim such a backbone for cancer prevention.

A model – and a message – for the world

What Rwanda has built is not a one-size-fits-all blueprint, but a demonstration that elimination is possible when all three pillars are addressed through strong systems, political will, and community trust. The model reflects Rwanda’s own context – its universal health insurance, cohesive community-health network, and integrated digital infrastructure – elements not always replicable elsewhere.

Yet it provides powerful inspiration for countries charting their own paths. Rwanda’s experience underscores a simple truth: elimination requires action across all three pillars – vaccinating girls, screening women, and treating precancerous lesions and invasive cancer early. Each pillar strengthens the others. Rwanda’s achievement lies not in copying a model, but in coordinating across systems to make prevention and care part of everyday life.

Early results are striking. Screening coverage has soared, treatment rates are climbing, and invasive cancers are being detected earlier. Every precancerous lesion treated represents a potentially life-threatening cancer prevented – a quiet victory in a global fight that too often leaves women behind.

When the WHO called for the elimination in 2020, it offered a vision of a world where no woman dies from a preventable cancer. Rwanda has shown that vision can be engineered into reality.