“There’s a lady whose kids used to fall ill from malaria every now and then. After three months, she said, ‘you know what? Since you’ve placed these products here, I’ve never gone to the hospital.’”

Lucy, a community health worker with the AEGIS project

“When you consider that each malaria infection in a child is a life-threatening event, you understand the urgency.”

Dr. Eric Ochomo, Principal Investigator at KEMRI, a partner on the AEGIS Kenya trial.

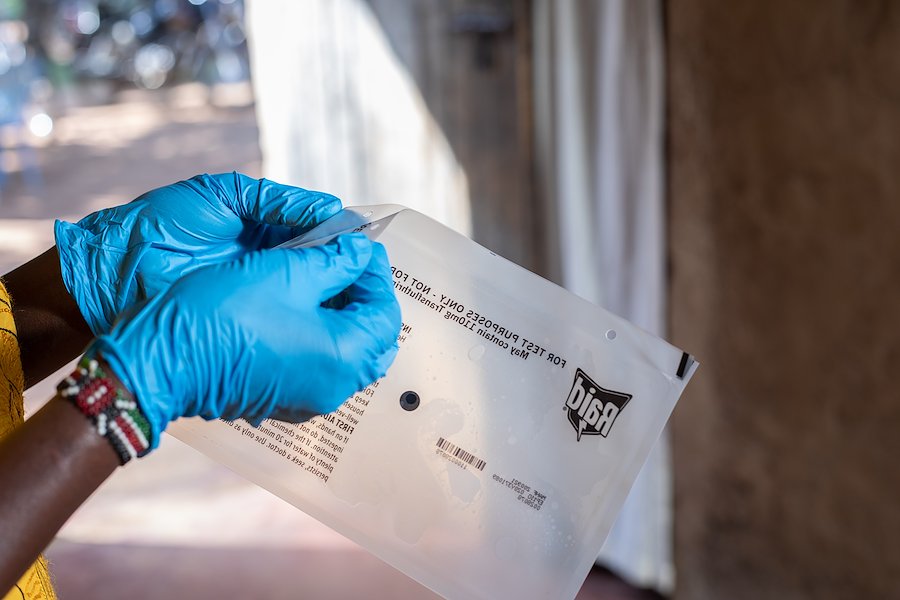

Now, the fight against malaria could welcome the first new vector control intervention in decades. Unitaid’s AEGIS project, led by the University of Notre Dame, aims to validate the use of spatial repellents in combatting malaria through research programs in Kenya, Mali and Uganda.

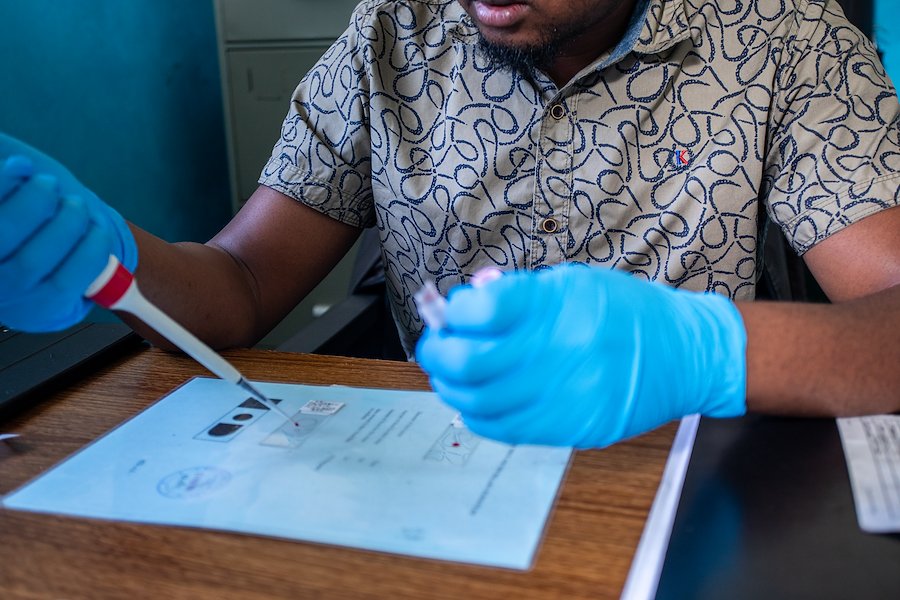

The WHO requires results from at least two clinical trials in distinct contexts to be able to fully evaluate the public health value of new tools and issue a recommendation – a critical step in unlocking broad access to the products through major scale-up partners. Results from the Kenya trial have demonstrated efficacy, fulfilling the first of the required evidence.

But in Busia County in Kenya, communities have urged their government not to wait. Here, rates of malaria hover around 40% – mirroring malaria rates of countries with the highest burden – and people are eager for new ways to protect themselves and their children.

“When you consider that each malaria infection in a child is a life-threatening event, you understand the urgency,” explains Dr. Eric Ochomo, Principal Investigator at the Kenyan Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), a partner on the AEGIS Kenya trial. Dr. Ochomo himself was born in an area of Kenya that experiences high rates of malaria. His mother was so severely ill with malaria while pregnant with him that he was born two months prematurely. He was one of the lucky ones; two of his siblings died within days of their births because of complications from malaria.

“It’s incredibly exciting to see so much enthusiasm from affected communities for this new tool.”

Kelsey Barrett, Technical Manager in Unitaid’s Strategy team.

Though mosquito nets and indoor spraying are in use in these malaria-endemic areas of Kenya, they are not always enough to keep infections at bay, Dr. Ochomo says. “For example, some parts of Western Kenya are prone to flooding and for this reason indoor residual spraying isn’t an option. When community groups saw the impact our clinical trial was having, they began to call for access to spatial repellents.”

They managed to contact their member of parliament, prompting the Ministry of Health to approach Dr. Ochomo and the KEMRI team. With early positive results from the AEGIS trial guiding their work, the KEMRI team sat down with Ministry of Health officials and other malaria experts to develop the very first national implementation strategy for spatial repellents.

“It’s incredibly exciting to see so much enthusiasm from affected communities for this new tool,” says Kelsey Barrett, Technical Manager in Unitaid’s Strategy team. “When we design grants, our goal is to address the access barriers that may slow a product down or stop it from reaching those that need it most. The collaboration between the researchers, community advocates and the Kenyan government spurring rapid roll-out is a best-case result.”

Insecticide-treated nets, particularly the latest next-generation products that use dual insecticides, remain critically important vector control tools, but spatial repellents show promise in providing additional protection in some settings, explains Dr. Nicole Achee, a Medical Entomologist at the University of Notre Dame and Scientific Director of the AEGIS project.

“Mosquitoes continue to be a problem mostly at night, but there are some types that bite at different times. Meanwhile, the behavior of other mosquitoes is changing, and more biting is happening in the evening or early morning when a person may not be sleeping and is less likely to be protected by a bed net,” explains Dr. Achee.

Insecticide resistance and logistics pose additional challenges.

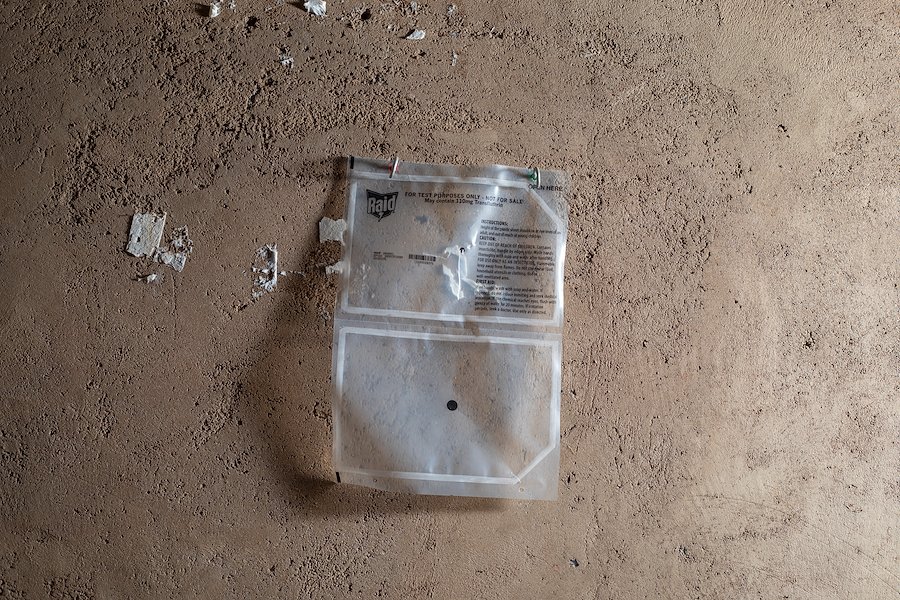

Mosquitoes and the malaria parasites they transmit adapt very quickly, causing chemical products to become less effective over time. Because mosquito nets come into such close contact with people, updating the insecticides used on them requires rigorous safety testing. Spatial repellents, which hang out of reach, are easier and faster to safely adapt when resistance develops.

Spatial repellents are also light-weight and compact, facilitating their reach into remote communities. And with a new large-scale manufacturing site set to open in Nairobi later this year, SC Johnson, the company that produces the spatial repellents, will base product distribution from this major transport hub at the geographic heart of the fight against malaria.

SC Johnson’s continued investment into spatial repellents has led to the development of a next-generation product that remains effective against mosquitoes for a full year – a major improvement on the once-monthly product that has already shown so much promise in the Kenya trial.

And as climate change expands areas at risk of malaria and increases natural disasters and displaced communities, new vector control tools suitable for deployment in these diverse settings are increasingly critical, says Unitaid’s Kelsey Barrett.

“There are still a lot of unanswered questions about how and where spatial repellents could be most useful,” she says. The AEGIS project is conducting research in Uganda to understand how spatial repellents could be used in refugee camps or other humanitarian settings and evaluating if they could also be used against the mosquitoes that transmit diseases like dengue through another clinical trial in Sri Lanka.

Unitaid’s recent call for project proposals looks to answer additional questions on how and where to effectively deploy spatial repellents and how best to integrate them into existing malaria control strategies, while helping create a viable market for the new products.

“For me, it’s a personal story. The changes to the malaria response that we’re seeing affect myself and my family directly.”

Dr. Eric Ochomo, KEMRI

The results from the Kenya trial are expected to be published in the second half of 2024. Meanwhile in Kenya, the government will begin rolling out spatial repellents in the new year, covering all areas where malaria persists despite the use of bed nets or other first-line vector control interventions.

“I’m glad to see this moving forward,” says Dr. Ochomo. “I think the spatial repellent has arrived at the opportune moment and I’m glad to be part of the research that is helping advance this.

“For me, it’s a personal story. I’ve seen how much of a problem malaria is for our people. The changes to the malaria response that we’re seeing affect myself and my family directly.”