Yet this region also harbours many success stories. HIV medicines are readily available; the number of HIV infections has fallen; and deaths have been halved over the last decade.

Now Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is rolling out routine “viral load” testing in this region, part of an eight-country initiative funded by Unitaid. Most high-burden countries in Africa have very low access to viral load testing, which is now the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended approach to monitor the level of HIV in the blood. Machines are large, expensive and require skilled technicians to operate, putting them out of reach of millions in low-income and remote settings.

Innovations in Malawi offer a peek into a future where technology and good practices could bring such quality chronic HIV care to rural communities throughout Africa.

As part of Unitaid’s grant, MSF is piloting different ways to implement viral load testing in the rural areas of Southern Malawi and get results quickly to patients and caretakers. Above, a health surveillance assistant takes a blood sample at the Bvumbwe Health Centre in Thyolo district, a large, remote area with an HIV prevalence rate of approximately 14-16%.

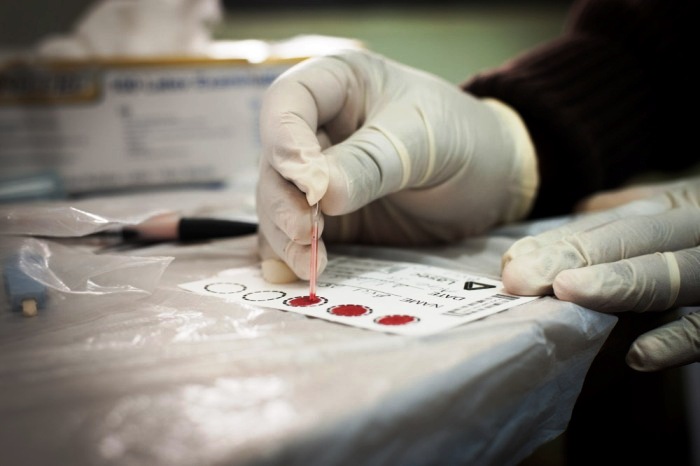

The health worker then prepares a dried blood spot (DBS) sample. Previously used mainly for infants, DBS reduces the complexity of transporting samples from rural areas.

Samples are collected from decentralized sites, and then delivered by motorbike to the Thyolo District Hospital, above, where they are analysed in the laboratory. Viral load results are sent back to health workers via SMS. Malawi’s experience in using DBS will provide a critical example for other countries. “We are influencing policies nationally and internationally and other districts are coming to see our good work,” said the Thyolo District Medical Officer, Dr Michael Murowa.

Above, at the National Association for People Living with HIV/AIDS in Malawi (NAPHAM) support group in the remote village of Chidothe in Thyolo. This community-based initiative brings together patients to take turns on a rotating basis to collect antiretrovirals every month. The Chidothe support group also discusses adherence issues and positive living – recently they’ve learned the importance of viral load testing.

Ennet Manda, 49, is a member of NAPHAM. Living with HIV for seven years, she has one child and four grandchildren. She recently had a viral load test and was proud to say that she was “undetectable.”

At the Namitambo Health Centre, pictured above in the remote Chiradzulu District, MSF is rolling out SAMBA, the first available point-of-care viral load device, as part of the Unitaid grant. Chiradzulu has an HIV prevalence rate of approximately 17% and throngs of HIV patients crowd the complex.

Inside a small brick building, health workers take blood samples and run them through the SAMBA machine. SAMBA can be rolled out in more peripheral health care facilities and is the first of a rich pipeline of point-of-care technology [PDF, 2.8 MB] to be deployed at this level.

Laboratory clerk, Violet Jombo, is pictured above, reviewing viral load counts measured with SAMBA. One strong advantage of point-of-care devices is that they require limited staff training, which will help to overcome severe staff shortages of laboratory technicians in many low-income countries.

One woman, Mercy Banda, walked 7 km to the Namitambo Health Centre to get her viral load test. Clinicians suspected her treatment was failing, and tested Mercy’s blood, using SAMBA, as she waited outside. If Mercy’s viral load was found to be over 1,000 copies per ml, clinicians would start three months of adherence counselling, working together with Mercy to help her take medications.

Despite these innovations, the majority of devices that provide essential HIV monitoring are large and based in central laboratories. This is particularly true for the highly-sensitive molecular testing that is needed for babies born to HIV-positive mothers. Infants retain maternal antibodies against HIV for over a year after birth. Specialized diagnostics known as “early infant diagnostics” are needed to analyse RNA and DNA in a baby’s blood sample.

Above, an EID machine in Malawi’s commercial capital Blantyre. This large machine conducts EID testing for all of Southern Malawi. Drivers leave the hospital once a week to pick up samples from rural areas.

A new version of SAMBA is being rolled out in select African countries that can now provide EID testing at the point-of-care, meaning mothers and healthcare workers can get a child’s results the same day. Identifying babies and putting them on treatment early is critical – without treatment one-third of children born with HIV die in their first year of life.

All photos: © Giulio Donini/Unitaid